Whether you are an adult citizen or non-citizen, you have certain rights if you are arrested. Before the law enforcement officer questions you, he or she should tell you that:

You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say may be used against you. You have a right to have a lawyer present while you are questioned. If you cannot afford a lawyer, one will be appointed for you. These are your “Miranda” rights, guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution. If you are not given these warnings, your lawyer can ask that any statements you made to the police not be used against you in court. But this does not necessarily mean that your case will be dismissed. This does not apply if you volunteer information without being questioned by the police.

The purpose of an arrest is to bring the arrestee before a court.

The federal Constitution imposes limits on both civil and criminal arrests.

An arrest may occur (1) by the touching or putting hands on the arrestee; (2) by any act that indicates an intention to take the arrestee into custody and that subjects the arrestee to the actual control and will of the person making the arrest; or (3) by the consent of the person to be arrested.

The test used to determine whether an arrest took place in a particular case is objective, and it turns on whether a reasonable person under these circumstances would believe he or she was restrained or free to go. A reasonable person is one who is not guilty of criminal conduct, overly apprehensive, or insensitive to the seriousness of the circumstances. Reasonableness is not determined in light of a defendant’s subjective knowledge or fears. The subjective intent of the police is also normally irrelevant to a court’s determination whether an arrest occurred, unless the officer makes that intent known. Thus, a defendant’s presence at a police station by consent does not become an arrest solely by virtue of an officer’s subjective view that the defendant is not free to leave, absent an act indicating an intention to take the defendant into custody.

Police officers need no justification to stop someone on a public street and ask questions, and individuals are completely entitled to refuse to answer any such questions and go about their business. However, the Fourth Amendment prohibits police officers from detaining pedestrians and conducting any kind of search of their clothing without first possessing a reasonable and articulable suspicion that the pedestrians are engaged in criminal activity. Terry v. Ohio 392U.S. 1, 88 S. Ct. 1868, 21 L. Ed. 889 (1968). Police may not even compel a pedestrian to produce identification without first meeting this standard.

Similarly, police may not stop motorists without first having a reasonable and articulable suspicion that the driver has violated a traffic law. If a police officer has satisfied this standard in stopping a motorist, the officer may conduct a search of the vehicle’s interior, including the glove compartment, but not the trunk, unless the officer has probable cause to believe that it contains contraband or the instruments for criminal activity.

Investigatory stops or detentions must be limited and temporary, lasting no longer than necessary to carry out the purpose of the stop or detention. An investigatory stop that lasts too long turns into a de facto arrest that must comply with the warrant requirements of the Fourth Amendment. But no bright line exists for determining when an investigatory stop becomes a de facto arrest, as courts are reluctant to hamstring the flexibility and discretion of police officers by placing artificial time limitations on the fluid and dynamic nature of their investigations. Rather, the test is whether the detention is temporary and whether the police acted with reasonable dispatch to quickly confirm or dispel the suspicions that initially induced the investigative detention.

Not all arrests are made by members of law enforcement. Many jurisdictions permit private citizens to make arrests. Popularly known as citizen’s arrests, the circumstances under which private citizens may place each other under arrest are normally very limited. All jurisdictions that authorize citizen’s arrests prohibit citizens from making arrests for unlawful acts committed outside their presence. Most jurisdictions that authorize citizen’s arrests also allow citizens to make arrests only for serious crimes, such as felonies and gross misdemeanors, and then only when the arresting citizen has probable cause to believe the arrestee committed the serious crime. Witnessing the crime in person will normally establish probable cause for making an arrest.

Both private citizens and law enforcement officers may be held liable for the tort of false arrest in civil court. An action for false arrest requires proof that the process used for the arrest was void on its face. In other words, one who confines another, while purporting to act by authority of law which does not in fact exist, makes a false arrest and may be required to pay money damages to the victim. To make out a claim for false arrest, the plaintiff must show that the charges on which he or she was arrested ultimately lacked justification. That is, the plaintiff in a false arrest action must show that the arrest was made without probable cause and for an improper purpose.

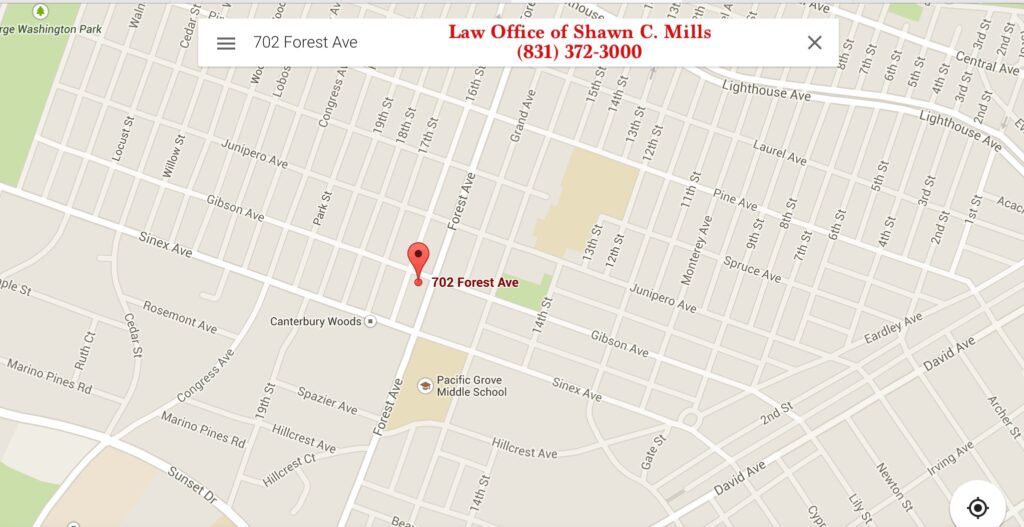

Shawn C. Mills, Attorney at Law #189893

MONTEREY CRIMINAL DEFENSE SERVICES

702 Forest Avenue, Suite A

Pacific Grove, CA 93950

(831) 372-3000 or

(831) 521-Six-Two-Six-Five